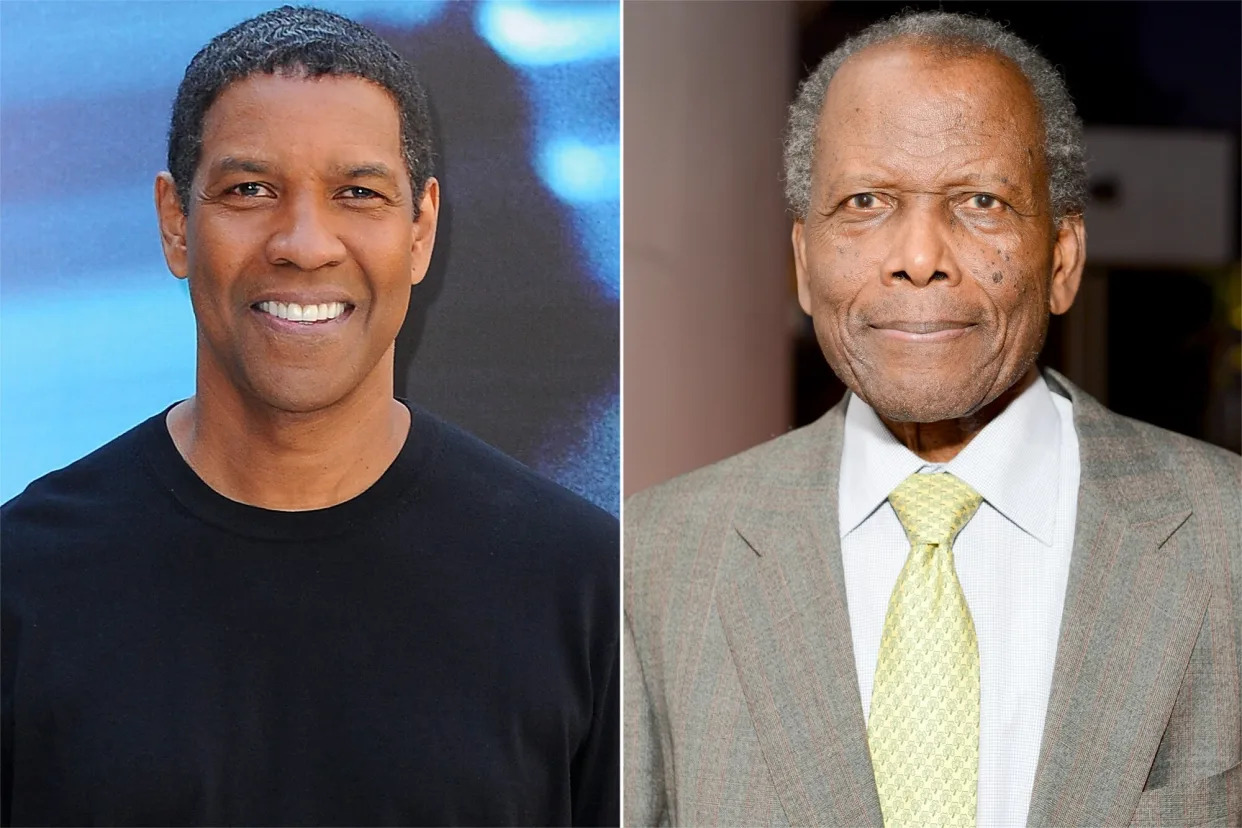

(Video) Denzel Washington Reveals Why Oprah WANTED Sidney Pitier GONE!

In the glitzy realm of Hollywood, where stars rise and fall like shooting comets, Sidney Poitier stood as a towering figure among black actors.

However, even despite his opening doors for future black actors and being an epitome and role model to others, some black celebrities are working hard to undo all that his presence in Hollywood accomplished.

Watch video:

His trailblazing legacy paved the way for countless aspiring talents, serving as a beacon of hope and inspiration.

Oprah Talks to Sidney Poitier

Photo: Kwaku Alston

The legendary actor and director opens up about what five decades in Hollywood have taught him—and why his biggest challenge has been to be his own person.

Just hearing the word “linoleum” makes me recall the exact moment that awakened me to my possibilities: Milwaukee. 1964. My mom’s place. I am 10 years old, black people are still “colored”—and colored folks don’t ride in limousines unless their kinfolk have just died. I press my knees into the cold linoleum and stare into our RCA black-and-white TV. My mouth falls open as a towering Sidney Poitier steps from a limo and into the Academy Awards. Awe. Freeze. Thaw. Run. “Everybody, come see: A colored man is in a limo—and nobody’s died!” The next day—the next moment—I see myself in an entirely new way. Thirty-six years later, I get to tell Sidney Poitier what that moment meant to me.

“In my spirit I knew that because you had won the Oscar, I too could do something special—and I didn’t even know what it was,” I say. “I thought, ‘If he can be that, I wonder what I can be.'” Poitier and I are sitting across from each other at the Bel-Air hotel in Los Angeles—and I’m admiring that, at 73, this man still personifies grace, ease, strength and courage. He is a gentleman in every sense of the word. In my more than 25 years as an interviewer, I’ve talked to hundreds of people—yet today, I’m giddy. When I admit this to him, he grins. “That flatters me,” he says. “I’ve never done anything to warrant that.”

Not so. The youngest of seven children, Poitier lifted himself from extreme poverty—his parents were tomato farmers who worked on Cat Island in the Bahamas, where they had no running water or electricity. At 15 and with no education, he went to live with his older brother in Miami, Florida, where he had an encounter with the Ku Klux Klan. A few months later, he arrived in New York with only $3, and then he answered an ad seeking actors for the American Negro Theatre. But when he flubbed his lines and spoke in a thick Caribbean accent, the director told him, “Stop wasting your time—get a job as a dishwasher!”

The rejection galvanized Poitier. After months of mimicking American newscasters in order to lose his accent and of working in exchange for acting lessons, Poitier returned to the same theater company and landed a role in Days of Our Youth. That began his ascent to becoming one of the most bankable actors of any race. In his 50 years in film, he has starred in and directed more than three dozen movies whose titles read like a time line for our memories: The Defiant Ones, 1958; A Raisin in the Sun, 1961; Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and To Sir, With Love, both in 1967. And when he won an Academy Award for his performance in the 1963 film Lilies of the Field, Poitier changed film history: He became the first and only black person to receive an Oscar for best actor.

However remarkable his achievements, Poitier will tell you that he doesn’t measure himself by these things—really. Especially during the Civil Rights movement when nonblacks often defined him solely in terms of race—and conversely, when some black people branded him an Uncle Tom who wasn’t enough of a race revolutionary—Poitier’s fight became not about race but about self—”In America,” he tells me, “it is difficult to be your own man.” But by focusing on the big picture—the breadth of who he is as a man, not confined by color—he has indeed embraced the fullness of his humanity.

Poitier and I talk about the convictions his parents passed on to him and how his family perceives him. He has four daughters from his marriage to his first wife, dancer Juanita Hardy; he and his second wife, Canadian actress Joanna Shimkus-Poitier, have been married since 1976 and have two daughters. When Sidney and I part, I weep—he leaves me feeling expanded, more hopeful and more human, and willing to engage in the complete arc of life. And after sitting with him through four hours of conversation, I am still in awe of him—and I am as inspired as I was as a 10-year-old colored girl colored girl.

Oprah: Growing up, your identity was about what you could offer as a human—and that was not connected to color. By the time you came to this country, you knew who you were. Weren’t you 15 when you came here?

Sidney: Yes. But even when I was younger—11, 12, 13—I knew consciously who I was.

Oprah: And who were you?

Sidney: A boy who had a relationship with silence. I learned to hear silence. That’s the kind of life I lived: simple. I learned to see things in people around me, in my mom, dad, brothers and sisters. At that time, there were only about 1,000 people on Cat Island. And no one ever told me, “You must be careful because there are things out there that are not friendly [for blacks].”

Oprah: So you didn’t know yourself in the context of color?

Sidney: I had no idea. There were two whites on our island. One was a doctor, another a shopkeeper’s daughter. And it never dawned on me that they were anything but people.

Oprah: So the word white was just an identification—like the word tall?

Sidney: Absolutely. White didn’t mean power, so I wasn’t prepared for anything out there that would not be friendly.

Oprah: And you weren’t prepared for anyone who did not see you in the same way you saw yourself.

Sidney: Yes. Never in my early years was I told, “Be careful how you walk down the street.” I never had to be conscious of stepping off the sidewalk to let someone pass. So I’ve got to tell you, I had no idea what was waiting for me in Florida. When I arrived at the age of 15, almost everything I heard said to me, “There are different values here. Here, you are not the person you think you are.” But I came with 15 years of preparation. I was strong enough to say to myself, “The me that I’ve been for 15 years—I like that me! That’s a free me. I can’t adjust to being a restricted me.” The law said, “You cannot work here, live here, go to school here, shop here.” And I said, “Why can’t I?” And everything around me said, “Because of who you are.” And I thought, I’m a 15-year-old kid—and who I am is really terrific! Luckily, I had the beginnings that I did. And every time [restrictions] were in my face, I could say, “Let me remind you who I am.”

Oprah: I read in your memoir, The Measure of a Man, that when you began acting, you were offered a role that you turned down because it contradicted your values, even though the role paid $750 a week. Can you tell the story?

Sidney: I was married with a young child, and I had one child on the way. I needed the bucks! The role was a janitor, to which I had no objection. This janitor worked for a gambling casino. Someone connected with his company was killed, and it was thought that the janitor had information about the death. The people who perpetrated the crime went to the janitor and said, “It is imperative that you don’t speak of whatever you may know.” Then the bad people, in order to cement their control over the janitor, killed his daughter. They threw her body on his lawn, and he didn’t do anything. Mind you, the script implied that he was devastated….

Oprah: But the character did nothing?

Sidney: Nothing. And I could not imagine playing that part. So I said to myself, “That’s not the kind of work I want.” And I told my agent that I couldn’t play the role. He said, “Why can’t you play it? There’s nothing derogatory about it in racial terms,” and I said, “I can’t do it.” He never understood.

Oprah: Was this Marty?

Sidney: Yes. Marty Baum, my agent. I didn’t want to have to explain it. It was stupid! My daughter Pam was about to be born, and Beth Israel Hospital had told my wife and me that it would be $75 to cover the birth. I didn’t have the money. So when I left Marty’s office, I went to a place called Household Finance on Broadway near 57th Street, and I borrowed against our furniture.

Oprah: You turned down $750 a week and then borrowed against your furniture?

Sidney: Right.

Oprah: What did your wife say?

Sidney: She was a very supportive person. She was a different kind of person than I was, but she knew it meant a lot to me to be the way I was.

Oprah: Were you thinking, “I’m a man defined by character, and this is something I won’t do”? And is that how you made all your film choices?

Sidney: Every one. I had two roles for which I compromised.

Oprah: What were they?

Sidney: One was Porgy and Bess, the other was The Long Ships.

Oprah: Why do you feel that Porgy and Bess was a compromise?

Sidney: I was in the Caribbean making a picture with John Cassavetes. There was no telephone on the island, so I would take a four-hour trip to St. Thomas and go to a hotel to call home, then my agent. On one such trip, Marty said, “We’ve got a problem.” His West Coast co-agent had gotten a call from [film producer] Sam Goldwyn, who had said, “I want Sidney Poitier to play Porgy. Can you get him for me?” and the co-agent said, “I’ll get him for you.” That went public quickly, and mind you, I’m away, so I don’t know anything about this. After Marty told me, I said, “Just call Mr. Goldwyn and tell him that I’m not going to play the part.”

Oprah: Because you didn’t like what it represented?

Sidney: Yes. And Goldwyn said to Marty, “Why don’t you have Sidney come out and talk with me, and if he tells me that he doesn’t want to do it, then I’ll know that he means it.” So when I finished my movie, I went to California to see Sam. And I told him as respectfully as I could that I couldn’t play the part. He said, “Do me a favor: Go back to New York and think about it for two weeks.” And I said, “But I know now!” And he said, “Just think about it.” When I went back to my hotel, there was a script waiting for me called The Defiant Ones. I read the script in one sitting and said to Marty, “This is something I’d like to do. Tell Mr. Goldwyn that I’d like to meet with Stanley Kramer”—the guy who wants me to do this movie. So I went to see Stanley, and he said, “I would love to have you play in it, but you have a problem—Sam Goldwyn.” Sam was one of the most powerful men in the entire industry. And having having gone public with the news that I may play the Porgy role, he had put himself on the line.

Oprah: And he could not be embarrassed.

Sidney: He wouldn’t have stood for it. So I got a call from Hedda Hopper [the famous Hollywood columnist]. She said, “I know Sam, and he’s in a tough position. If you don’t do his picture, he’ll see to it that you never work in this town again.”

Oprah: Wow!

Sidney: So I had a lot of thinking to do, and I agonized. And I couldn’t come to a conclusion. Finally, Marty and I came up with the only thing I could do, because I wanted to do The Defiant Ones. I did one movie, Porgy and Bess, so I could do the other. It was painful, but it was useful. I learned some lessons, and if I had it to do again, I wouldn’t do it any differently, because I had work to do.

Oprah: Oh my goodness, Sidney—if you hadn’t done it, I wouldn’t have been on that linoleum floor watching you get out of the limousine! And I might not be here today. So what did doing Porgy and Bess teach you?

Sidney: That it is difficult to be your own man in America. There is a fierce requirement to adjust to circumstances.

Oprah: Wasn’t that just the nature of Hollywood at the time?

Sidney: It was difficult. [Blacks] were so new in Hollywood. There was almost no frame of reference for us except as stereotypical, one-dimensional characters.

Oprah: Maids and buffoons. And obviously, you weren’t going to play any role that negated the character of blacks.

Sidney: Not only was I not going to do that, but I had in mind what was expected of me—not just what other blacks expected but what my mother and father expected. And what I expected of myself.

Oprah: And what was that expectation?

Sidney: To walk through my life as my own man. I’d seen my father. He was a poor man, and I watched him do astonishing things. After the tomato business failed [on Cat Island], he moved to Nassau with no money. He moved there with rheumatoid arthritis, and I saw him hang on to his dignity day by day. And it was hard, because there, if you had nothing, you got no respect. Yet he never lost his dignity. And in his lifetime, my father never earned as much money as I spend in a week.

Oprah: I read that shortly after you were born, you weren’t expected to live because you were delivered so prematurely.

Sidney: I was expected to be dead within two, three days. I was born two months early, and everyone had given up on me. But my mother insisted on my life. She went throughout the black sections of Miami, where I was born, looking for help to save her child. She went to the church, and she went to the few people she knew. Absolutely heavyhearted, my mom passed a fortune-teller’s stall, and she sat with this lady. She said, “I need you to tell me about my son.” And the woman said, “Don’t worry about your son. He will not be a sickly child. He will walk with kings. He will step on pillars of gold. And he will carry your name to many places.”

Oprah: What was your mother’s name?

Sidney: Evelyn. I was a gift to my mother. She was a remarkable person. God or nature, or whatever those forces are, smiled on her, then passed me the best of her.

Oprah: Did she live long enough to reap the benefits of your life?

Sidney: She lived long enough to see me win the Academy Award. And that was tremendous.

Oprah: Did she understand what that was?

Sidney: Not altogether. But she figured it out, because when I arrived in Nassau, the people gave me a parade around the island, and she thought that was swell. The thing that best describes my mother is that, subsequent to me winning the Academy Award, she would go around the neighborhood, and whenever she’d see a mother chastising her kid, she would say, “You be careful with that child—my Sidney used to act that way.”

Oprah: So you have carried her name?

Sidney: I have carried her name—a name I was asked to change.

Oprah: You were asked to change your name?

Sidney: When I went into the business, the name Poitier was thought to be difficult.

Oprah: I was asked to change my name, too!

Sidney: Were you?

Oprah: The name Oprah was thought to be too different. In my first job, they wanted me to call myself Susan.

Sidney: My goodness!

Oprah: Susan!

Sidney: When I was asked to change my name, I said no. I wouldn’t. I couldn’t. So, back to my mother—I cannot take credit for who I turned out to be. I have had that woman on my shoulder all my life. You hear? She has been there taking care of me. I am not a hugely religious person, but I believe that there is a oneness with everything. And because there is this oneness, it is possible that my mother is the principal reason for my life.

Oprah: I also believe in that oneness. Didn’t you feel a greater sense of your mother’s presence after she’d passed? Because when people die, their energy doesn’t leave you, if you’re open to it. And so of course your mother has been on your shoulder. That’s why you couldn’t have lost.

Sidney: I was helped.

Photo: Kwaku Alston

Oprah: And having a mother who loves you—there’s nothing stronger.

Sidney: We should not limit it to two generations. I have to accept that my contribution to the man that I have become was a small one. The gift made to my mother, which manifested in me, could have been lying in dormancy across generations. Because let me tell you, my dear—there is something about you that didn’t just happen when your father’s sperm hit your mother’s egg. The sperm and egg carry a history that includes generations you don’t know. Take a person like Stevie Wonder, who was blind from a young age. Where did his gifts come from? His mother? They came through her. And it is conceivable that 5, 10 or 20 generations ago there was someone with an extraordinary gift in Stevie’s family, but the external circumstances of that person’s life were such that they never gave rise to the gift’s blossoming.

Oprah: Because it takes a combination of forces to bring out gifts.

Sidney: Exactly. One day, it happens: A kid like Stevie is walking through a living room, and there is a piano, and he hears a note, and it becomes the light. So the journey is not one generation. Each of us is an accumulated effort unfolding.

Oprah: That’s why it’s exasperating when people continue to see you only in the context of race.

Sidney: I deal with race-based questions all the time, but I resent them. I will not let the press thrust me into a definition by feeding me only race questions. I’ve established that my concern with race is substantive. But at the same time, I am not all about race. I have had to [deal with this] all my career. And I’ve had to find balance. So much was riding on me as one of the first blacks out there.

Oprah: As Quincy Jones says, you created and defined the African-American in film.

Sidney: It’s been an enormous responsibility. And I accepted it, and I lived in a way that showed how I respected that responsibility. I had to. In order for others to come behind me, there were certain things I had to do.

Oprah: Did you know you were a hero?

Sidney: Listen—

Oprah: Sidney, you were more than just the first. By your choices, you became heroic.

Sidney: And you know what? I—

Oprah: Sidney, just take it! Say, “You know what, Oprah? You’re right. Damn, I was a hero—and I still am!”

Sidney: I cannot, and I’ll tell you why. If I were to be judged by my father—

Oprah: Who is still the standard-bearer for you?

Sidney: Yes. And that’s my whole compass. You see?

Oprah: Because you feel this way, isn’t it frustrating when others define you in terms of color?

Sidney: It doesn’t aggravate me anymore, but it did. I was fortunate enough to have been raised to a certain point before I got into the race thing. I had other views of what a human is, so I was never able to see racism as the big question. Racism was horrendous, but there were other aspects to life. There are those who allow their lives to be defined only by race. I correct anyone who comes at me only in terms of race. For instance, I have friends who don’t know many blacks. And sometimes, a friend will say how well he or she knows a black person.

Oprah: I grew up in an environment where I was often the only black child, and people would ask me if I knew you!

Sidney: You ready for this? I’ve been told, “You look like Sammy Davis Jr.”

Oprah: Could the person who said this see? Or was it Stevie Wonder?

Sidney: That joke brings to the fore the fact that others’ knowledge of blacks is far from multidimensional. And our difficulties should teach us to see the big picture. The big picture is that racism has been an awful experience—but there are other experiences. We need to keep an eye on the other human experiences to give ourselves the fullness and the breadth of our own humanity. Our humanity is served back to us through the eyes of those who have diminished us. And they serve back to us a view of ourselves that is incomplete. If we don’t look to the bigger picture, our view will narrow to that which is constantly fed to us.

Oprah: You’re saying everything that I believe! We define our own lives, and we become what we believe. That’s why there were people who were enslaved who could say inside themselves, “This is not who I am. I’m gonna go north, though I’m not sure which way that is.”

Sidney: Absolutely. And what troubles me is that so many people don’t know how to get ahold of their sense of self, that sense that says, “I am—and I need to strengthen this me.”

Oprah: In Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, it felt as if you wrote that speech your character says to his father, who objects to your character marrying a white woman. Do you remember the speech?

Sidney: Of course.

Oprah: Some people forget their parts.

Sidney: No, no, no. That speech meant so much to me. It was how I felt. My character says to his father, “I love you, Dad. You’re my father. But there’s this difference: I think of myself as a man, and you think of yourself as a colored man.”

Oprah: So back to a question I wanted to get to: How did you feel when your own people labeled you an Uncle Tom and a “millionaire shoeshine boy” in the sixties?

Sidney: It was hurtful. You cannot help but be hurt. It was far from the truth, but I understood the times. There was a public display of all the rage that [blacks] had built up over centuries. If you examine the movies, the criticism I received was principally because I was usually the only black in the movies. Personally, I thought that was a step!

Oprah: And wasn’t it in 1967 that you were the highest-ranking actor of any color?

Sidney: True.

Oprah: And so as a step, I think that’s pretty major!

Sidney: Yes! But it was the times. Even Dr. King was branded an Uncle Tom because of the rage.

Oprah: So when people called you an Uncle Tom, did you just think, “Now is my time to have people turn on me”?

Sidney: I lived through people turning on me. It was painful for a couple years…. I was the most successful black actor in the history of the country. I was not in control of the kinds of films I would be offered, but I was totally in control of the kinds of films I would do. So I came to the mix with that power—the power to say, “No, I will not do that.” I did that from the beginning. Back then, Hollywood was a place in which there had never been a To Sir, With Love, The Defiant Ones, In the Heat of the Night or Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Nothing like it. What the name-callers missed was that the films I did were designed not just for blacks but for the mainstream. I was in concert with maybe a half-dozen filmmakers, and they were all white. And they chose to make films that would make a statement to a mainstream audience about the awful nature of racism.

Oprah: And it was your choice to play in these films.

Sidney: My choice. That’s how my career started. Every one of those pictures, with the exception of the two I mentioned earlier, came from filmmakers who had to make a comment that racism is wrong. There are people—black, white, blue, green—who find it necessary to make that kind of comment through their lives or professions. And I was a part of that mix. I was privy to the big picture—a lot of people aren’t. So I can’t put people down because they were frustrated.

Oprah: In the late sixties, there was a scathing New York Times article, headlined “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier?” in which playwright Clifford Mason blasted you for pandering to whites. Did the criticism you received for the roles you played cause you to do any soul-searching?

Sidney: I’ll tell you what I did: I went down to the Bahamas, and I went fishing. I thought about things, and I knew that I was at a crossroads in my career.

Oprah: Really?

Sidney: Yes. I decided that I must learn everything I could about the production of motion pictures. In a way, I had always been doing that by watching directors, but I decided I wanted to make films. I entered an agreement with Paul Newman, Steve McQueen and Barbra Streisand. We started a film production company called First Artists. I did four movies with them. I did Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again and A Piece of the Action. I did A Warm December as well. I set out to make films that would get people to laugh at themselves without cringing. Then I went on to direct other films, such as Stir Crazy. I’ve been a principal player in motion pictures for more than 50 years. That’s a longevity that makes a statement. And my body of work in those 50 years is a testament to those producers who had the courage to step out during the tough years. It’s a testament to my values.

Oprah: Sidney, what do you do for fun?

Sidney: I play a lot of golf. My love of golf far outstrips my gift for it, but I love it. And I read a lot.

Oprah: What do you read?

Sidney: I love James Baldwin—the way he put words together. And Shakespeare for being such a wordsmith. I’ve read so many books on astronomy. I’ve also read Aristotle and Plato.

Oprah: And you didn’t have any formal education, right?

Sidney: No.

Oprah: That’s why it’s so extraordinary that you could hold on to who you are!

Sidney: You know what? It was survival.

Oprah: All the work I do is about helping people realize who they are. The whole quest for each of us is to become more of who we are meant to be. So how does someone get to that?

Sidney: We all have different selves: There is a public self, a private self and a core self. We all know the public self—it’s how we put our best foot forward, smiling and behaving. But the private self is a more fundamental self, and that is where we find our frailties, our fears. It’s like a clearinghouse where our demons are safe. Then there’s the core self, which is our pure instinct. That’s where all our goodness and capacity for kindness lives. You can feel it sometimes. When people say, “I feel it in my stomach,” that’s the core self. Our best comes from there, and we know how courageous and honorable we are. The core self is who we are.

Oprah: How do you learn to trust that core self?

Sidney: I don’t know how to do that for other people—I know how to do it for me. And I keep searching for answers.

Oprah: You once said that you have been visited by regrets. Other than playing Porgy, what do you regret?

Sidney: When I was a boy on Cat Island, I used to go hunting with a slingshot. And I would hit birds with my pebbles. Later in life, I learned the value of a life. I wanted to be my own man, but I wasn’t allowing the birds I destroyed a life. I had to go back and examine my killing of those birds, frogs and insects.

Oprah: No, you didn’t.

Sidney: I surely did, my darling! And you know what? I learned that an insect, a frog, a bird are such miraculous creations, and who am I to destroy them since I cannot create them? Do you know what goes into the design of a little beetle that flies? There I was, killing them at random! And the remorse helped me to never kill again.

Oprah: I’m with you. But I can tell you for a fact that I do not feel a thing for flies. I am not that evolved. Do you save flies?

Sidney: If a fly’s on my arm, I will brush near it.

Oprah: But you won’t hit it?

Sidney: I wouldn’t swat it.

Oprah: Now that is honor beyond that which I know.

Sidney: I have this feeling that life is so magically created that if I respect it, that respect will come circling back to me in ways I don’t even know.

Oprah: I believe that. Now I must go home and mourn the flies I’ve killed! Sidney, how is it that you never appeared to be angry?

Sidney: Let me tell you about anger. I don’t express it to people, to family, to friends. I know better than most about the devastating results of humiliation. I know how soul-destroying rejection is. I walked into a hotel once, and there was a famous emcee standing there. He was speaking with some friends, and I stood aside and admired him. At a moment when I thought I wouldn’t be disturbing him, I walked up and said, “Excuse me, may I please have your autograph?” He didn’t say anything. He just looked at me with an annoyed look, like I was wasting his time. I was frozen. Finally, he reached out in a disparaging way and took my paper and pen, scribbled something and passed it back to me. I felt awful, awful, awful. I collect those moments, just like I collected my regrets about the birds. And having to carry that moment inside me produced a certain response, and as a result, I am never too rushed to give someone an autograph.

Oprah: Never?

Sidney: I will stop. And if I’m running to catch a plane, I will say to the person, “Please jog with me.” I don’t want to be the agent of passing that feeling to anybody.

Oprah: Have you been able to pass on all of your wisdom and honor to your children?

Sidney: I live my life as we have discussed, and my children see that. After I won the Screen Actors Guild award [for lifetime achievement], one of my daughters said to me, “You’re pretty good, Dad.” Now this is a kid who most of the time thinks I’m just an old fuddy-duddy, so I know when she says things like that, she’s saying a lot more.

Oprah: Would your children say you’re an easy dad to get along with?

Sidney: I think my children would be unlikely to say that I’m easy. But in general, I’m perceived as a person who’s relatively easy to get along with.

Oprah: Would your wife, Joanna, agree with that statement?

Sidney: Yes. She would tell you that I’m a perfectionist to a degree and that I ask of others a certain kind of loyalty to and respect for relationships. My wife would say that, on occasion, I’m a little tough on the children.

Oprah: In what way?

Sidney: In what I expect and demand of them in terms of values. My children respect my values, and I can see some of those values in them. That pleases me, because my values are not constricting. They are human values. My kids are quite intelligent—all six of them.

Oprah: You’ve said that you want to keep growing. Is there anything else you want to do in your life?

Sidney: I would like to grow less afraid of dying. I am infinitely less afraid today than I was 15 or 25 years ago. I was most afraid of dying when I was 33, because I come from a Catholic family.

Oprah: And Jesus was crucified at 33?

Sidney: Yes.

Oprah: I went through that, too. You think, “If Jesus can die at 33, who am I?”

Sidney: Right.

Oprah: Would you prefer to be diagnosed with a long-term illness as opposed to passing on suddenly?

Sidney: I would like to die like my mother did. She was walking about the house, and she said to my sister, “Make me a cup of tea and bring it to me, I’m going to take a nap.” It took my sister two or three minutes to get the tea, and when she walked into the bedroom, my mother was gone.

Oprah: How old was she?

Sidney: Sixty-eight. She was gone in three minutes, and that was a blessing. I hope I’m that deserving.

Oprah: We earn everything in our lives. Do you think we also earn our death?

Sidney: I won’t speculate on that, because death is so sacred a state of being.

Oprah: I think it’s interesting that you would have any fear about death, since you’re not killing flies! Whatever happens, you’ll get the best end of it.

Sidney: I’d like to meet my end with grace.

Oprah: And don’t you know you will, since you’ve met everything else in your life with grace, Sidney?

Sidney: I shall certainly try my best to meet it with grace. There is always the element of anxiety about it, but that anxiety lessens over the years.

Oprah: It doesn’t increase as you age?

Sidney: It decreases. If you are anxious about death, then you don’t have a sense of the oneness of things—you feel that after death, you will be no more.

Oprah: Right. What else would you like to do in the coming years?

Sidney: I’d like to write, act, teach, lecture—anything creative. I must also service my curiosity. I want to continue to wonder about things, because there is a young man inside me, and he is energetic and mentally active.

Oprah: So being 73 means kapooey to you? It’s all those soy products!

Sidney: I can examine so many things. I would like to do independent thinking about everything—to just sit and think independently about things.

Oprah: That’s fantastic. I’m not there yet.

Sidney: I am right there.